Elementor #2077

Bridging Gaps: My Journey from Limited Access to Open Science Excellence

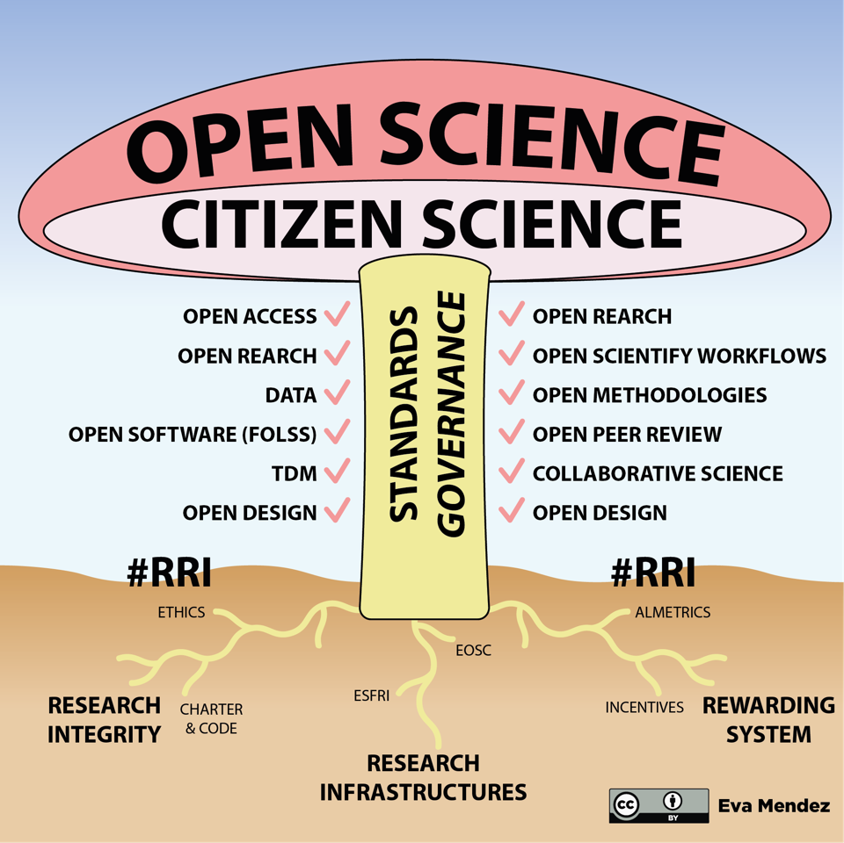

When I graduated in engineering in Cuba in 2016, access to scientific information was incredibly limited. Our research on optical and biomechanical models of the human eye, in collaboration with the National Ophthalmology Institute, faced many challenges due to these limitations. Lack of internet access, connectivity, access to publications, code licenses, etc., prevented us from collaborating and keeping up with global advances. However, thanks to a course on open science taught by Eva Mendez, my perspective on research has changed radically. This course has revolutionized the way I approach, share and seek knowledge.

Recently, I have participated in the course “Ticket to Open Science” organized by UC3M and led by Prof. Dr. Eva Méndez and Pablo Sánchez. As a researcher and PhD candidate, this course has profoundly influenced my views on open science practices. this course covered a wide range of topics, including data management plans (DMPs), open access publishing, FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable and Reusable) data principles and responsible research evaluation. We also explored various digital tools and platforms, such as GitHub, Zenodo and OpenAIRE, that facilitate the sharing and accessibility of research data and publications. The course emphasized the importance of transparency, collaboration and accessibility in scientific research, providing practical guidance on the application of these principles in our daily work.

The course emphasized the importance of open science. This improves the reproducibility of my work and facilitates collaboration. In my NEREIDA project, I applied FAIR principles to data generated from neutron simulations and experimental measurements. By ensuring that the data were well documented, properly indexed and stored in accessible repositories such as GitHub, I will make it easier for other researchers to find and reuse the information, thereby boosting collaborative efforts and improving the overall impact of our work.

One of the main obstacles to research is the accessibility of publications. The course reinforced my commitment to open access publishing, using platforms such as OpenAIRE to democratize knowledge. This not only fosters an inclusive research environment, but also accelerates scientific progress. All these features of open science will be incorporated into the NEREIDA Project during my doctoral training. This integration will facilitate collaboration with other institutions, increasing the reach and impact of the project. Open science also promotes collaboration and partnerships with institutions such as the National Atomic Energy Commission (CNEA) in Argentina, the Nuclear Safety Council (CSN), the Latin American Giant Observatory (LAGO) with its wide distribution throughout Latin American countries, and the Bariloche Atomic Center. These collaborations increase the reach and impact of my research, fostering a more interconnected scientific community with more resources.

Responsible evaluation of research was another crucial issue. Advocating for new evaluation policies at my institution is essential to creating a system that values transparency, accessibility, and collaboration.

My experience in the Ticket to Open Science course has been enlightening. Open science is not just a fad; it is a necessity for the advancement and democratization of scientific knowledge. As researchers, we must embrace these practices and lead the shift to a more collaborative and accessible future. A gap of limitations has been filled in my life, I would have liked to apply these principles and tools in my past research in Cuba.

I thank UC3M, Professor Dr. Eva Mendez, Pablo Sanchez and all the course participants for this enriching experience. I look forward to applying these principles in my work and contributing to a more open and equitable future in science.

Forward to Open Science!

Osiris Núñez